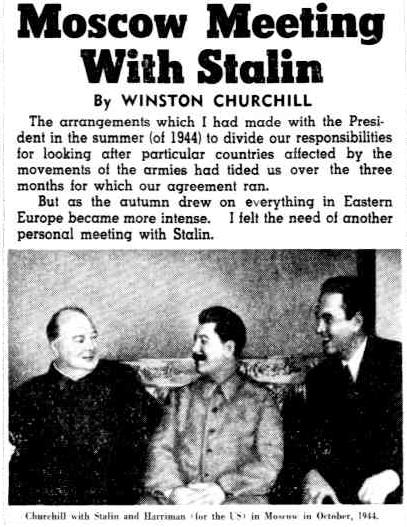

President Roosevelt liked my plan of going to Moscow, and Stalin sent me a cordial invitation. […] We alighted on Moscow on the afternoon of October 9, and were received very heartily and with full ceremonial by Molotov and many high Russian personages. At 10 o’clock that night we held our first important meeting in the Kremlin. It was agreed to invite the Polish Prime Minister, M. Romer, the Foreign Minister and M. Grabsch, a grey bearded and aged academician of much charm and quality, to Moscow at once.

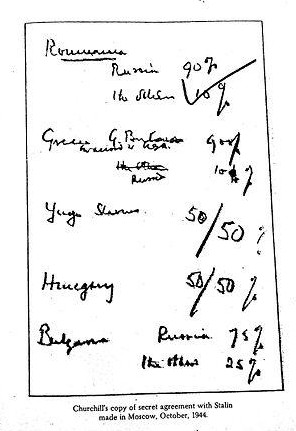

[…] The moment was apt for business, so I said: “Let us settle about our affairs in the Balkans. Your armies are in Rumania and Bulgaria We have interests, missions and agents there. Don’t let us get at cross purposes in small ways. So far as Britain and Russia are concerned, how would it do for you to have 90% predominance in Rumania, for us to have 90% of the say in Greece, and go fifty-fifty about Yugoslavia?” While this was being translated I wrote out on a half-sheet of paper:

Rumania (Russia 90%, the others 10%); Greece (Great Britain in accord with USA 90%, Russia 10%); Yugoslavia (50-50); Hungary (50-50); Bulgaria (Russia 75%, the others 25%). I pushed this across to Stalin, who had by then heard the translation. There was a slight pause. Then he took his blue pencil and made a large tick upon it, and passed it back to us. It was all settled in no more time than it takes to set down. Of course we had long and anxiously considered our point, and were only dealing with immediate war-time arrangements. All larger questions were reserved on both sides for what we then hoped would be a peace table when the war was won. After this there was a long silence. The pencilled paper lay in the centre of the table. At length I said, “Might it not be thought rather cynical if it seemed we had disposed of these issues, so fateful to millions of people, in such an offhand manner? Let us burn the paper?”“No. you keep it” said Stalin.

[«Al presidente Roosevelt piacque il mio piano di recarmi a Mosca, e Stalin mi aveva inviato un cordiale invito. […] Arrivammo a Mosca nel pomeriggio del 9 ottobre, accolti calorosamente con tutti i crismi del cerimoniale da Molotov e altre illustri personalità russe. Alle 10 di quella sera abbiamo tenuto la nostra prima importante riunione al Cremlino. È stato deciso di invitare immediatamente a Mosca il primo ministro polacco, M. Romer, il ministro degli esteri e M. Grabsch, un accademico dalla barba grigia e dal grande carisma.

[…] Il momento sembrava appropriato per gli affari, così ho detto: “Mettiamoci d’accordo sui Balcani. I vostri eserciti sono in Romania e in Bulgaria. Laggiù abbiamo interessi, missioni e agenti. Non fateci prendere decisioni unilaterali. Per quanto riguarda la Gran Bretagna e la Russia, cosa pensate di questa proposta: voi vi tenete il 90% della Romania, noi ci teniamo il 90% della Grecia, e spartirci a metà la Jugoslavia?”. Mentre le mie parole venivano tradotte, scrivevo su un foglietto di carta:

Romania (Russia 90%, gli altri 10%);

Grecia (Gran Bretagna in accordo con USA 90%, Russia 10%);

Jugoslavia (50-50);

Ungheria (50-50);

Bulgaria (Russia 75%, gli altri 25%).

Passai poi il foglietto a Stalin, che aveva già ascoltato la traduzione. Ci fu una brevissima pausa. Prese la penna, vi fece un segno sopra e ce lo restituì. Avevamo impiegato meno tempo a prendere la decisione che a trascriverla.

Ovviamente avevamo ponderato a lungo le nostre richieste, e al momento ci stavamo accordando solo su problemi immediati, imposti dal tempo di guerra. Le questioni più spinose erano invece rimandate al tavolo di pace che speravamo sarebbe scaturito dalla nostra vittoria in guerra. Dopodiché ci fu un lungo silenzio. Il foglio appuntato giaceva al centro del tavolo. Alla fine dissi: “Non sembra un po’ cinico aver preso queste decisioni, fatidiche per milioni di persone, in un modo così improvvisato? Che facciamo, bruciamo la carta?”

“No, la tenga lei”, disse Stalin.»]

(Winston Churchill, “The Advertiser”, 7 Novembre 1953)